Zimbabwe with Mavros Safaris | Prestige Hong Kong (Dec 18)

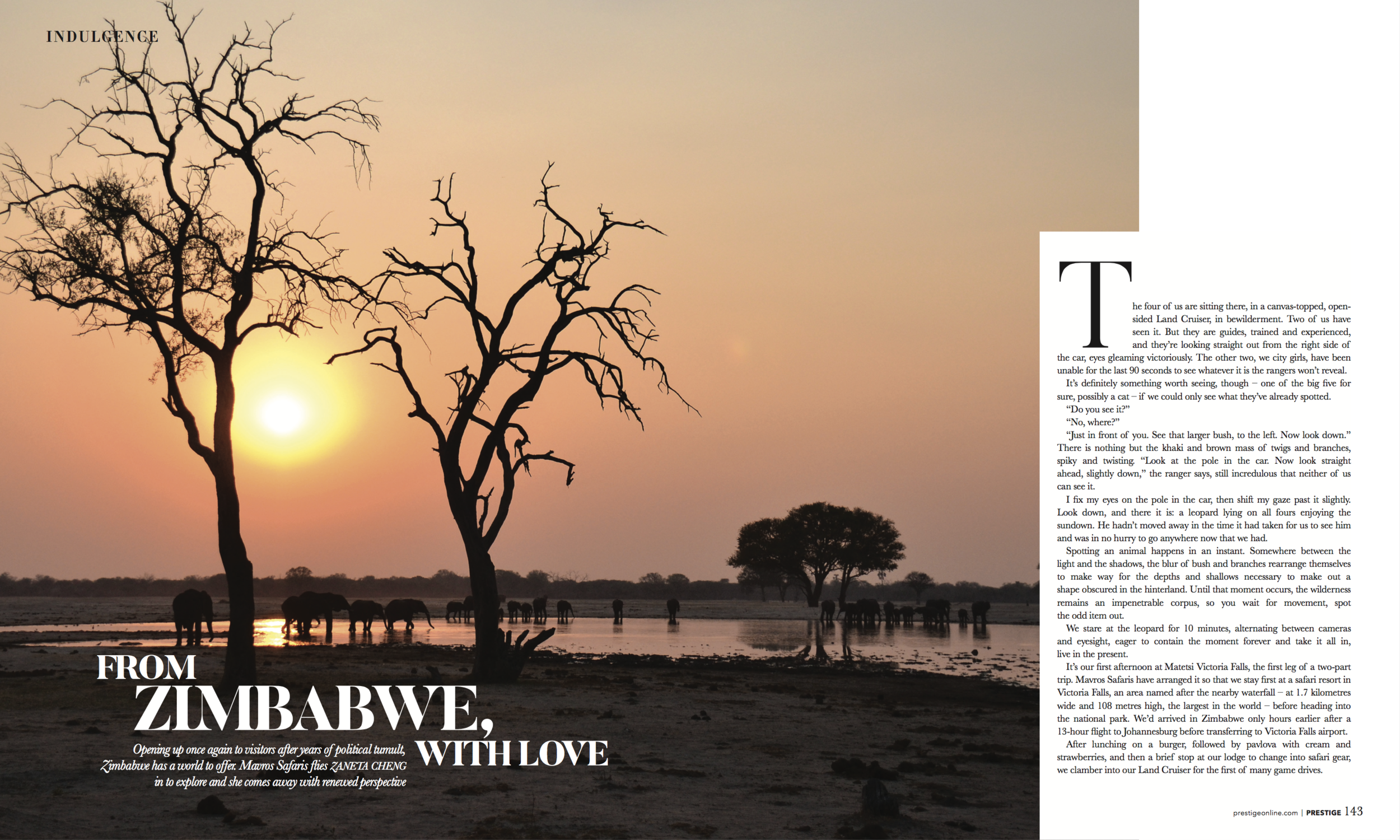

Opening up once again to visitors after years of political tumult, Zimbabwe has a world to offer. Mavros Safaris flies zaneta cheng in to explore and she comes away with renewed perspective

The four of us are sitting there, in a canvas-topped, open-sided Land Cruiser, in bewilderment. Two of us have seen it. But they are guides, trained and experienced, and they’re looking straight out from the right side of the car, eyes gleaming victoriously. The other two, we city girls, have been unable for the last 90 seconds to see whatever it is the rangers won’t reveal.

It’s definitely something worth seeing, though – one of the big five for sure, possibly a cat – if we could only see what they’ve already spotted.

“Do you see it?”

“No, where?”

“Just in front of you. See that larger bush, to the left. Now look down.” There is nothing but the khaki and brown mass of twigs and branches, spiky and twisting. “Look at the pole in the car. Now look straight ahead, slightly down,” the ranger says, still incredulous that neither of us can see it.

I fix my eyes on the pole in the car, then shift my gaze past it slightly. Look down, and there it is: a leopard lying on all fours enjoying the sundown. He hadn’t moved away in the time it had taken for us to see him and was in no hurry to go anywhere now that we had.

Spotting an animal happens in an instant. Somewhere between the light and the shadows, the blur of bush and branches rearrange themselves to make way for the depths and shallows necessary to make out a shape obscured in the hinterland. Until that moment occurs, the wilderness remains an impenetrable corpus, so you wait for movement, spot the odd item out.

We stare at the leopard for 10 minutes, alternating between cameras and eyesight, eager to contain the moment forever and take it all in, live in the present.

It’s our first afternoon at Matetsi Victoria Falls, the first leg of a two-part trip. Mavros Safaris have arranged it so that we stay first at a safari resort in Victoria Falls, an area named after the nearby waterfall – at 1.7 kilometres wide and 108 metres high, the largest in the world – before heading into the national park. We’d arrived in Zimbabwe only hours earlier after a 13-hour flight to Johannesburg before transferring to Victoria Falls airport.

After lunching on a burger, followed by pavlova with cream and strawberries, and then a brief stop at our lodge to change into safari gear, we clamber into our Land Cruiser for the first of many game drives.

Generally, a game drive is directed by a tracker and a ranger. The ranger – who’s usually a human encyclopaedia – leads, driving us through the thick of the bush, spotting tracks, animals and faeces from the car. The duty of the tracker, who’s secondary to the ranger and sits on the car bonnet, is to spot even the tiniest of God’s living creatures and to draw our attention to it.

For example, there are trees right across the bush that look as if processionary caterpillars had run amok in the African landscape – a mistaken assumption on my part. My ranger tells me they’re in fact the nests of the white-browed sparrow weaver, built so as to confuse likely predators. Only one nest has eggs laid in it and it’s always to the west, as a counter to Zimbabwe’s prevailing easterlies.

Drives blur into each other, the thrill of the hunt taking over. We catch kudu and giraffe posing against the setting sun – waiting for pictures to be taken of them, their long lashes fluttering as they blink with the kind of languor that upwardly aspiring humans take years of posing to cultivate. There are elephant, buffalo, the African wild cat, an errant scrub hare, and springbok. At night, we hear hyena cackling, spot the giant eagle owl, its head twisting to glare at us before turning back, deeming us too trivial to care about. And, of course, the leopard.

No lens can capture the fierce vermillion of the sun melting into the horizon. No drawing or photograph can render the rays beaming across the blue-gold sky at dusk, dancing between the cotton-puff clouds. Indeed, no description can adequately convey the primal rush when your eye catches an animal in the wild. That adrenaline kick keeps safari junkies returning year after year – and it’s what keeps us out for hours on end, skipping meals over the course of the week, just to catch one more glimpse.

It’s also why Mavros Safaris has assembled a portfolio of lodges, camps and itineraries that enable clients to view animals while ensconced in comfort – the lap of luxury, even. At each destination, Land Cruisers and experienced guides are a given, but details such as blankets for the early morning chill and the bite of the evening breeze are also taken into consideration. Ponchos are at the ready, too, so the sudden, wet-season showers barely interfere.

Adrenaline tends to take its toll, so an hour into any drive refreshments are served at a safe place in the bush. Sometimes we snack on scones and biscuits as a family of chimps fight on the other side of the river. At others, we’re at the top of a hill overlooking a herd of buffalo on the “flay”, a vast savanna within the Matetsi Victoria Falls private concession. A ranger’s coffee is an indulgent necessity, fortified with a splash of Amarula Cream. I drink mine each morning dressed in a freshly laundered outfit – a standard courtesy at every safari camp and lodge.

Matetsi Victoria Falls sits on the southern bank of the Zambezi. While at lunch, we look across the river at Zambia and spot crocodiles skimming the surface of the water, as an impala bounds past our table. The resort is a series of lodges designed by Zimbabwean architect Kerry van Leenhoff to incorporate the country’s culture and nature. Dugout canoes greet guests when they walk into the open-air dining lodge. Indoor spaces connect with the outdoors via glass sliding doors. We don’t open ours much in our rooms but they’re convenient for when “George”, the local elephant, pays a visit to chow down on the tree beside our deck. There’s a private dipping pool and open shower along with the cavernous bathtub and shower indoors, which are godsends if you eschew an afternoon nap and venture to the falls instead.

There’s a seemingly unending list of things to do at Victoria Falls, from swimming at Devil’s Pool to bungee jumping – and it’s well worth everybody’s while to do at least some of them. Our way of taking it all in sees us embark on a short helicopter ride, a gorge swing and a tour, after which we partake of tea at the century-old Victoria Falls Hotel.

The gorge swing is among the more thrilling activities and perhaps the most scenic. The name, deceptively innocent, recalls playground frolics and, sandwiched between the terrifying bungee jump and the rather stultifying zipline, it seems to be the “just-right” option. Ignorance is my bliss and until the point of harness I refuse to face the facts. It turns out that a gorge swing is in fact a 70-metre free fall into the Batoka Gorge from a platform 120 metres above the water. I go ahead anyway, my ignorant leap of faith yielding one of the most breathtaking moments in my life: I count seven seconds before I reach the bottom, where I’m swinging above the Zambezi between two cliff faces.

Those boxes ticked, we spend the rest of our afternoons at Matetsi lazing at the lodge. There are activities such as canoeing and white-water rafting, but we station ourselves at the pool or spa. There’s no television, which we become grateful for, but there is Wi-Fi – something we’re also grateful for. We alternate between reading and watching monkeys scamper up to the rooftops to pick fruit from the trees – a special sort of bliss unknown to 21st-century city dwellers.

Not that we’re seeking respite from game drives, though these can be replaced by river cruises, which are better for spotting hippos peering out of the water or elephants coming down for a drink. A sunset cruise has a magic of its own but we realise we missed the thrill of speeding through the scrubland.

We dine at the lodge most evenings, classic British fare of steak, lamb chops or hake, perfectly prepared with vegetables and mash. But our most memorable evening is spent dining in the bush; it’s a delightful surprise for us, so I’ll keep it that way for you.

At night, turndown service draws a mosquito net around the bed. Luxury is in the details and the net doesn’t cling to the edge of the bed like so many do. Instead, a wooden frame helps it drape around the bedside tables and offers a good half-metre more space in the bug-free cocoon. Our 5am game-drive wake-ups are assuaged by tea and coffee delivered through the butler hole, and sipped to the strains of “The Circle of Life” and “Hakuna Matata” playing through a Bose speaker.

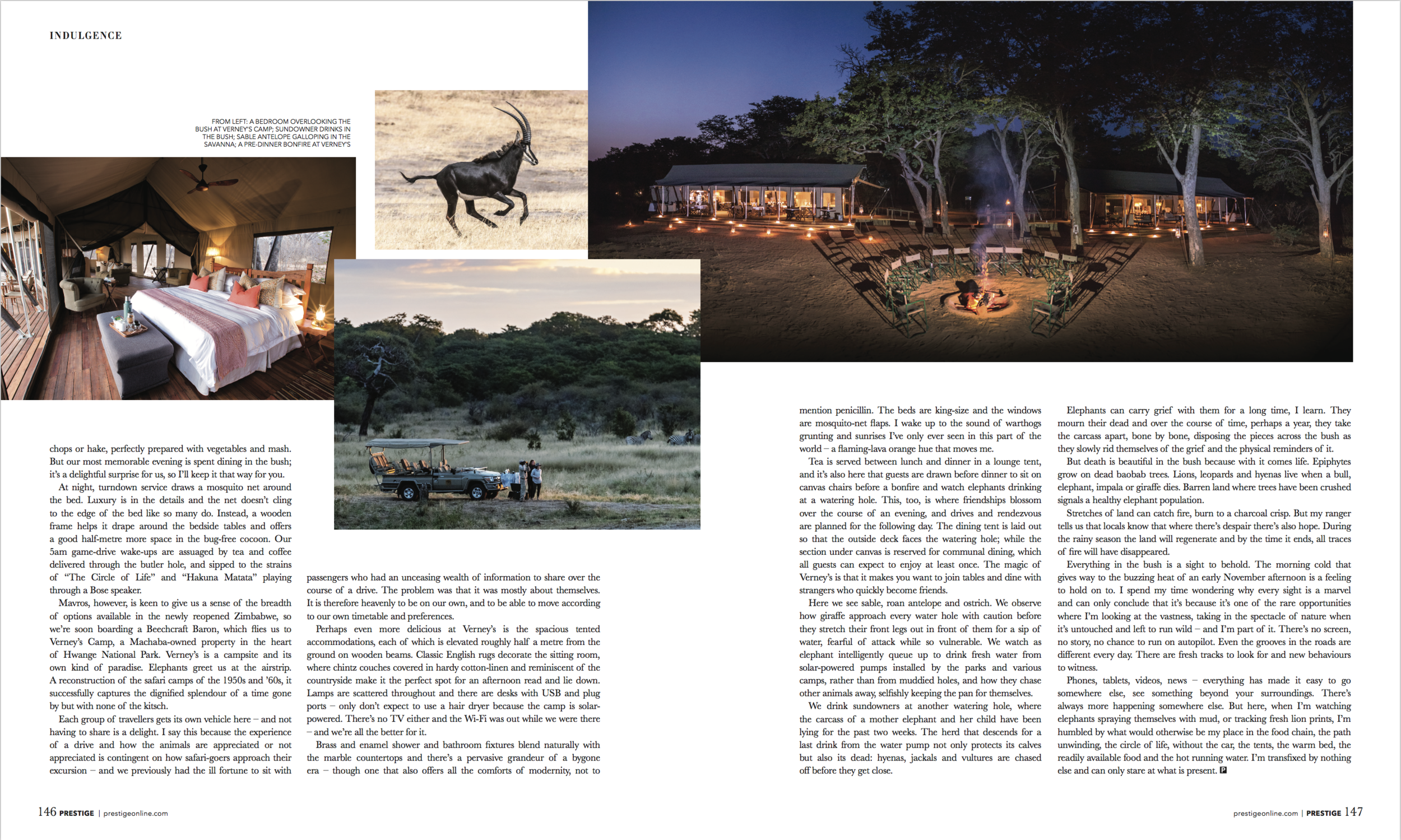

Mavros, however, is keen to give us a sense of the breadth of options available in the newly reopened Zimbabwe, so we’re soon boarding a Beechcraft Baron, which flies us to Verney’s Camp, a Machaba-owned property in the heart of Hwange National Park. Verney’s is a campsite and its own kind of paradise. Elephants greet us at the airstrip.

A reconstruction of the safari camps of the 1950s and ’60s, it successfully captures the dignified splendour of a time gone by but with none of the kitsch.

Each group of travellers gets its own vehicle here – and not having to share is a delight. I say this because the experience of a drive and how the animals are appreciated or not appreciated is contingent on how safari-goers approach their excursion – and we previously had the ill fortune to sit with passengers who had an unceasing wealth of information to share over the course of a drive. The problem was that it was mostly about themselves. It is therefore heavenly to be on our own, and to be able to move according to our own timetable and preferences.

Perhaps even more delicious at Verney’s is the spacious tented accommodations, each of which is elevated roughly half a metre from the ground on wooden beams. Classic English rugs decorate the sitting room, where chintz couches covered in hardy cotton-linen and reminiscent of the countryside make it the perfect spot for an afternoon read and lie down. Lamps are scattered throughout and there are desks with USB and plug ports – only don’t expect to use a hair dryer because the camp is solar-powered. There’s no TV either and the Wi-Fi was out while we were there – and we’re all the better for it.

Brass and enamel shower and bathroom fixtures blend naturally with the marble countertops and there’s a pervasive grandeur of a bygone era – though one that also offers all the comforts of modernity, not to mention penicillin. The beds are king-size and the windows are mosquito-net flaps. I wake up to the sound of warthogs grunting and sunrises I’ve only ever seen in this part of the world – a flaming-lava orange hue that moves me.

Tea is served between lunch and dinner in a lounge tent, and it’s also here that guests are drawn before dinner to sit on canvas chairs before a bonfire and watch elephants drinking at a watering hole. This, too, is where friendships blossom over the course of an evening, and drives and rendezvous are planned for the following day. The dining tent is laid out so that the outside deck faces the watering hole; while the section under canvas is reserved for communal dining, which all guests can expect to enjoy at least once. The magic of Verney’s is that it makes you want to join tables and dine with strangers who quickly become friends.

Here we see sable, roan antelope and ostrich. We observe how giraffe approach every water hole with caution before they stretch their front legs out in front of them for a sip of water, fearful of attack while so vulnerable. We watch as elephant intelligently queue up to drink fresh water from solar-powered pumps installed by the parks and various camps, rather than from muddied holes, and how they chase other animals away, selfishly keeping the pan for themselves.

We drink sundowners at another watering hole, where the carcass of a mother elephant and her child have been lying for the past two weeks. The herd that descends for a last drink from the water pump not only protects its calves but also its dead: hyenas, jackals and vultures are chased off before they get close.

Elephants can carry grief with them for a long time, I learn. They mourn their dead and over the course of time, perhaps a year, they take the carcass apart, bone by bone, disposing the pieces across the bush as they slowly rid themselves of the grief and the physical reminders of it.

But death is beautiful in the bush because with it comes life. Epiphytes grow on dead baobab trees. Lions, leopards and hyenas live when a bull, elephant, impala or giraffe dies. Barren land where trees have been crushed signals a healthy elephant population.

Stretches of land can catch fire, burn to a charcoal crisp. But my ranger tells us that locals know that where there’s despair there’s also hope. During the rainy season the land will regenerate and by the time it ends, all traces of fire will have disappeared.

Everything in the bush is a sight to behold. The morning cold that gives way to the buzzing heat of an early November afternoon is a feeling to hold on to. I spend my time wondering why every sight is a marvel and can only conclude that it’s because it’s one of the rare opportunities where I’m looking at the vastness, taking in the spectacle of nature when it’s untouched and left to run wild – and I’m part of it. There’s no screen, no story, no chance to run on autopilot. Even the grooves in the roads are different every day. There are fresh tracks to look for and new behaviours to witness.

Phones, tablets, videos, news – everything has made it easy to go somewhere else, see something beyond your surroundings. There’s always more happening somewhere else. But here, when I’m watching elephants spraying themselves with mud, or tracking fresh lion prints, I’m humbled by what would otherwise be my place in the food chain, the path unwinding, the circle of life, without the car, the tents, the warm bed, the readily available food and the hot running water. I’m transfixed by nothing else and can only stare at what is present.