Kris van Assche (Berluti) | Prestige Hong Kong (Apr 19)

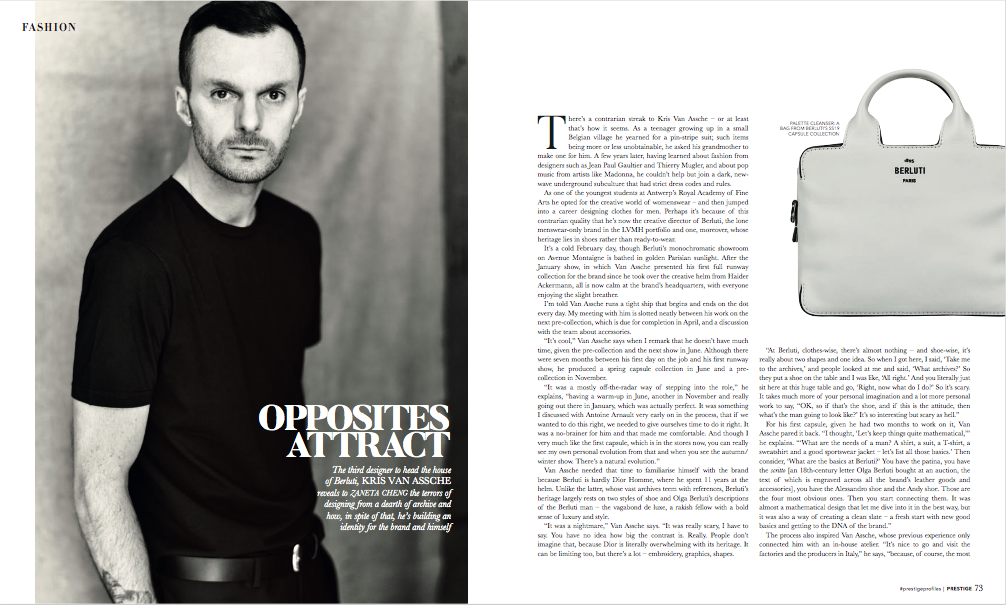

The third designer to head the house of Berluti, Kris van Assche reveals to zaneta cheng the terrors of designing from a dearth of archive and how, in spite of that, he’s building an identity for the brand and himself

There’s a contrarian streak to Kris Van Assche – or at least that’s how it seems. As a teenager growing up in a small Belgian village he yearned for a pin-stripe suit; such items being more or less unobtainable, he asked his grandmother to make one for him. A few years later, having learned about fashion from designers such as Jean Paul Gaultier and Thierry Mugler, and about pop music from artists like Madonna, he couldn’t help but join a dark, new-wave underground subculture that had strict dress codes and rules.

As one of the youngest students at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts he opted for the creative world of womenswear – and then jumped into a career designing clothes for men. Perhaps it’s because of this contrarian quality that he’s now the creative director of Berluti, the lone menswear-only brand in the LVMH portfolio and one, moreover, whose heritage lies in shoes rather than ready-to-wear.

It’s a cold February day, though Berluti’s monochromatic showroom on Avenue Montaigne is bathed in golden Parisian sunlight. After the January show, in which Van Assche presented his first full runway collection for the brand since he took over the creative helm from Haider Ackermann, all is now calm at the brand’s headquarters, with everyone enjoying the slight breather.

I’m told Van Assche runs a tight ship that begins and ends on the dot every day. My meeting with him is slotted neatly between his work on the next pre-collection, which is due for completion in April, and a discussion with the team about accessories.

“It’s cool,” Van Assche says when I remark that he doesn’t have much time, given the pre-collection and the next show in June. Although there were seven months between his first day on the job and his first runway show, he produced a spring capsule collection in June and a pre-collection in November.

“It was a mostly off-the-radar way of stepping into the role,” he explains, “having a warm-up in June, another in November and really going out there in January, which was actually perfect. It was something I discussed with Antoine Arnault very early on in the process, that if we wanted to do this right, we needed to give ourselves time to do it right. It was a no-brainer for him and that made me comfortable. And though I very much like the first capsule, which is in the stores now, you can really see my own personal evolution from that and when you see the autumn/winter show. There’s a natural evolution.”

Van Assche needed that time to familiarise himself with the brand because Berluti is hardly Dior Homme, where he spent 11 years at the helm. Unlike the latter, whose vast archives teem with references, Berluti’s heritage largely rests on two styles of shoe and Olga Berluti’s descriptions of the Berluti man – the vagabond de luxe, a rakish fellow with a bold sense of luxury and style.

“It was a nightmare,” Van Assche says. “It was really scary, I have to say. You have no idea how big the contrast is. Really. People don’t imagine that, because Dior is literally overwhelming with its heritage. It can be limiting too, but there’s a lot – embroidery, graphics, shapes.

“At Berluti, clothes-wise, there’s almost nothing – and shoe-wise, it’s really about two shapes and one idea. So when I got here, I said, ‘Take me to the archives,’ and people looked at me and said, ‘What archives?’ So they put a shoe on the table and I was like, ‘All right.’ And you literally just sit here at this huge table and go, ‘Right, now what do I do?’ So it’s scary. It takes much more of your personal imagination and a lot more personal work to say, “OK, so if that’s the shoe, and if this is the attitude, then what’s the man going to look like?’ It’s so interesting but scary as hell.”

For his first capsule, given he had two months to work on it, Van Assche pared it back. “I thought, ‘Let’s keep things quite mathematical,’” he explains. “‘What are the needs of a man? A shirt, a suit, a T-shirt, a sweatshirt and a good sportswear jacket – let’s list all those basics.’ Then consider, ‘What are the basics at Berluti?’ You have the patina, you have the scritto [an 18th-century letter Olga Berluti bought at an auction, the text of which is engraved across all the brand’s leather goods and accessories], you have the Alessandro shoe and the Andy shoe. Those are the four most obvious ones. Then you start connecting them. It was almost a mathematical design that let me dive into it in the best way, but it was also a way of creating a clean slate – a fresh start with new good basics and getting to the DNA of the brand.”

The process also inspired Van Assche, whose previous experience only connected him with an in-house atelier. “It’s nice to go and visit the factories and the producers in Italy,” he says, “because, of course, the most innovation is there. They’re competing with the outside world because they work with other brands. So these producers are constantly looking for new research, redefining new and better ways of making things.”

Berluti’s manifattura in Ferrara ultimately became one of Van Assche’s key sources of inspiration in determining his take on Berluti. “When I got to the manifattura, I was blown away. I always like a good contrast – I feel like contrasts give more strength to both messages, and that place is full of contrasts,” Van Assche recounts enthusiastically. “It’s the most modern, contemporary factory you’ve ever seen. So it’s beautiful, totally modern, yet on the inside people work things by hand. It’s very artisanal. So the shock between something really contemporary and something very traditional is super-inspiring.

“To have something really clean like the building and yet the patina on the tables – these tables get the colour from year after year of work and they ultimately became my show, but it’s another exigency, another level of luxury when you go there.”

Translating Berluti’s level of luxury into its new identity is something that Van Assche has enjoyed. “Olga Berluti told me that the Berluti guy was a vagabond of luxury – he knows about luxury but he has a free-spirited way of handling those rules and codes. If you put that alongside Berluti’s reputation for made-to-measure – that a lot of famous artists came to Berluti for hand-made shoes – you know they didn’t come for something neutral, they wanted character,” he says.

“The tricky part working at such a level of luxury – and when we work leather garments, I’m really like, ‘Wow!’ – is that people tend to think at this level, pieces should be timeless, which means non-fashion, because the idea of fashion is that pieces change, so when Olga told me people didn’t come to buy invisible pieces, that liberated me from that idea.”

The collection that came down the autumn/winter runway saw bright colours, patina, marbled coats and, most notably, a different silhouette – a departure from the slimmer couture cuts usually associated with Van Assche. “Here, the man is a little more rugged, a little more rough,” says the designer. “He’s about adventure, more seduction and that then creates a silhouette, but it’s a lot of sleepless nights to make that connection.

“But this needed to feel really Berluti for me, otherwise I feel disconnected. I don’t want to do my own brand here. So being able to take the marble table and extract the colours of it literally meant that at one point that colour was a Berluti product, otherwise there’s no reason why the patina would have penetrated the marble, so those are all ideas and colours that are part of the history of Berluti. And then I took those colours and they became suits and jackets and shirts and whatever. It’s a really big change for me because I’m not really such a colourful person, so that was super interesting.”

It’s also part of the reason why he chose to step into the role at the house. “I’m 42,” he says. “I need to put myself at risk, I need to reinvent myself, get out there and learn something. If it’s about the same silhouette, the same logic, the same process, then there’s nothing to learn. It’s a very selfish reason, actually, but I’ve already learned so much.”

But learning requires work – and I learn that in order for everyone to get evenings and weekends off, Van Assche packs in a full schedule during work hours. “Especially with this brand, how do you convince an intelligent person that you made a truly luxury product if you worked only a month on it? You need to put in the time to develop stuff. That means I’m here every day on the dot – and people need to prepare their dossiers and they need to be super-sharp.”

Just as I’m getting the sense that I’m talking to an army general, Van Assche quips, “I didn’t go to the army but I’ve been in the army for the last 20 years.”

Fashion and the military – now how contrarian is that?